The Power of Market-Creating Innovation

“Serious people laughed at me when I told them I wanted to build a telecommunications network in Africa twenty years ago. They told me all the reasons the project would never succeed,” Mo Ibrahim recalls of the reaction he received when he shared his plans to build a pan-African mobile phone company. “Somehow I just kept thinking, I know there are challenges but why can’t they see the opportunity?”

But Ibrahim, to his credit, saw things differently. Instead of only focusing on obstacles, he saw opportunity. In just six years, Celtel built operations in thirteen African countries—including Uganda, Malawi, the two Congos, Gabon, and Sierra Leone—and gained 5.2 million customers. At the openings of many of Ibrahim’s stores, it wasn’t uncommon to see eager customers line up by the hundreds. In 2005, when Ibrahim decided to sell the company, he did so for a handsome $3.4 billion. In such a short time, Ibrahim’s Celtel unlocked billions of dollars’ worth of value.

Market-Creating Innovation: A Game Changer for Economies

To understand why Ibrahim’s Celtel thrived, you need to understand the power and enormous potential of innovation—specifically, market-creating innovation. Not only do market-creating innovations develop new growth engines for companies, but they can also create entirely new industries upon which economies can build and thrive.

Market-creating innovations transform complex and expensive products into simple and more affordable alternatives, making them accessible to a whole new segment of people in society whom we call “nonconsumers.” Nonconsumers are individuals who have not yet been able to purchase a product or service that might help them solve a struggle in their lives simply because that product is not affordable or accessible to them. Market-creating innovations find a way to change that, creating new markets in the process. They represent the best version of capitalism, where both consumers and companies win.

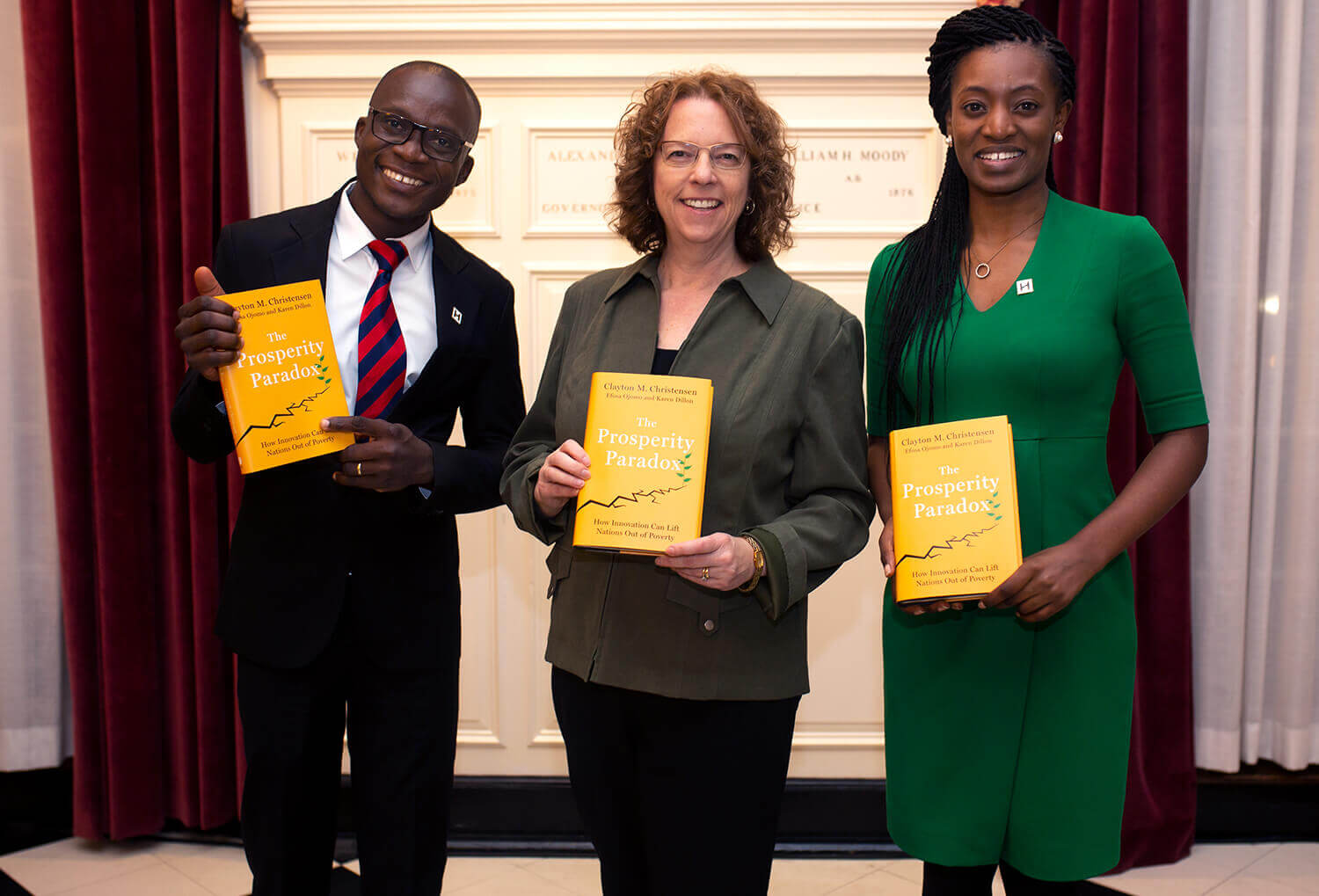

This concept is the central focus of The Prosperity Paradox: How Innovation Can Lift Nations Out of Poverty, which I co-authored with Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen and Efosa Ojomo H’17. Our research demonstrates that market-creating innovations can ignite the economic engine of a country. Successful market-creating innovations lead to three distinct outcomes:

- Job Creation: By their nature, they create jobs as more and more people are needed to make, market, distribute, and sell the new innovations.

- Public Service Funding: They generate profits from a wide swathe of the population, which can then be used to fund public services, including education, infrastructure, healthcare, and more.

- Cultural Change: They have the potential to shift the culture of entire societies.

Why More Entrepreneurs Haven’t Seized the Opportunity

If the potential of market-creating innovation is so obvious, why haven’t more entrepreneurs seized the opportunity? For some, the perceived obstacles to starting a business in developing economies are enough to deter them from trying. But as Ibrahim showed, market-creating innovators see those obstacles and find creative “work-arounds” that don’t deter the enormous opportunities to create new markets and businesses. These work-arounds are often rudimentary at first but get the job done. The Harambe Entrepreneur Alliance is filled with examples of companies that have done just that. More importantly, the Harambeans—innovators in the Alliance—are demonstrating the enormous potential of new markets in the process.

Innovating Healthcare in Rural South Africa: Dr. William Mapham’s Vula Mobile

Harambean Dr. William Mapham H’18, founder of Vula Mobile E Referral, developed an app to provide specialist care to rural healthcare workers in South Africa. The idea came from his own experience making long, difficult journeys to see patients in rural hospitals and clinics. Healthcare workers in these areas see an average of 3,000 patients a month but often lack access to the specialists they need. Mapham created a basic app that healthcare workers could download on their phones to relay questions to nearby specialists. The app is free for workers, with revenue coming from healthcare companies. Initially focused on eye care, Vula now serves 23 specialties and has helped over 150,000 patients. Mapham’s work demonstrates the potential of new markets and how technology can overcome infrastructure limitations.

Changing Financial Literacy with Fineazy: Monique Baars’ Innovation

Monique Baars H’19 saw the lack of financial literacy in South Africa as an opportunity to create a product for a new market. After working on a mobile financial services project at BCG, she launched Fineazy, a mobile service that teaches consumers about financial concepts like banking, loans, insurance, and investment. With two-thirds of the global population financially illiterate, Baars saw a clear need for accessible financial education. She created a chatbot-based service that uses storytelling to engage users. The stories follow characters like Yoofi, a university student who learns about financial decisions. Fineazy is free for consumers, and Baars’ paying customers are financial services companies wanting to reach a more educated consumer base.

The Road Ahead

Baars and her team continue to bridge the gap between existing institutions and the very real needs of “nonconsumers” in growing economies. She remains undaunted by the challenge: “Growing up in South Africa, I learned to innovate every day. I have no expectation that things will work, and when they do, I’m pleasantly surprised. I really believe in innovating around any problem. Anything is possible.”

About the Author

Karen Dillon is the former editor of Harvard Business Review and co-author of The Prosperity Paradox: How Innovation Can Lift Nations Out of Poverty with Clayton Christensen and Efosa Ojomo H’17.